22 Panels That Always Work: Wally Wood’s Legendary Productivity Hack

At 4/19/2024

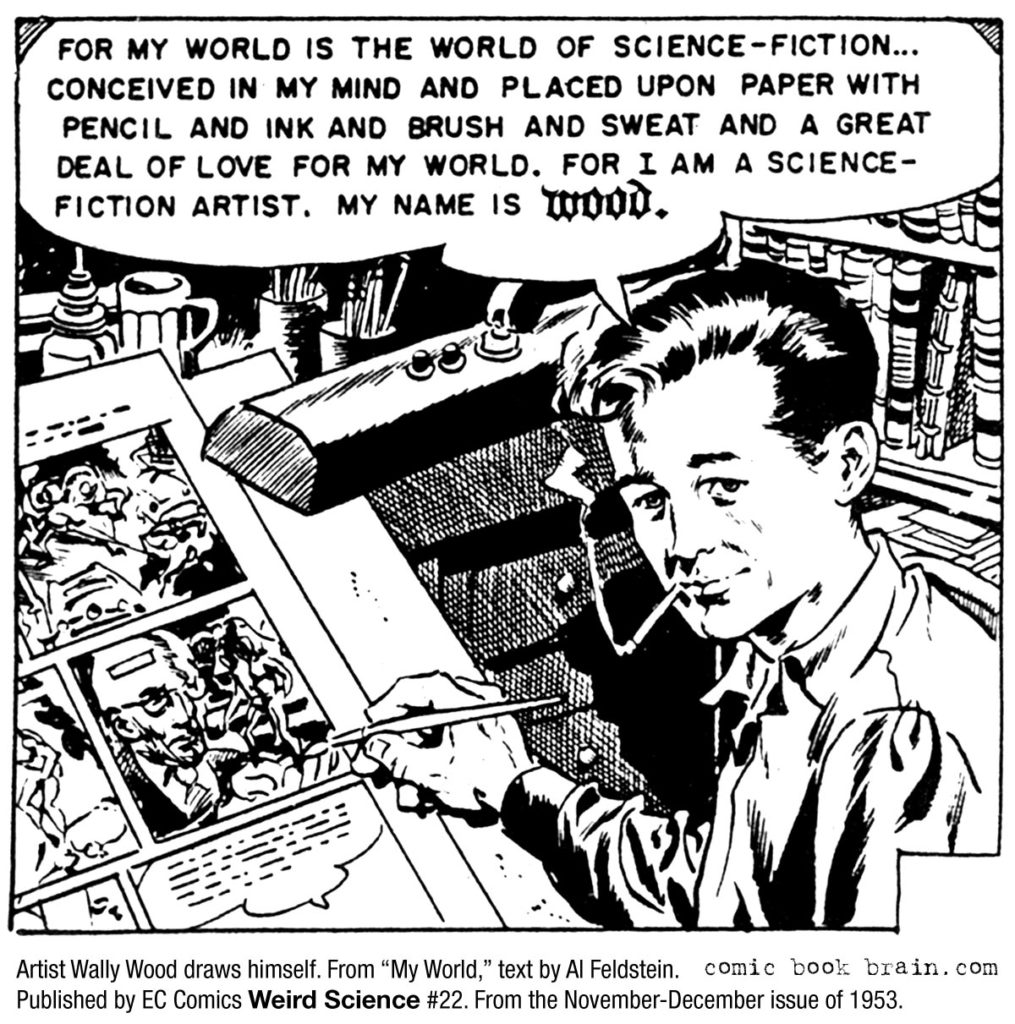

Wally Wood was an astonishingly talented and prolific artist during the Silver Age of comic books. He got his start professionally as a teenager in the late 1940s, drawing for EC Comic’s Weird Science and Weird Fantasy. In 1952 he contributed to the very first issues of MAD Magazine, and in 1964, he moved on to Marvel Comics.

According to his assistant Dan Adkins, at the time Wood was paid the highest rate in the industry. “$200 per page at MAD Magazine, where he was the most popular artist. When he quit MAD and went over to Marvel Comics, Marvel’s starting rate at the time was $20 per page to pencil and $15 per page to ink. Out of respect to Wally, they paid him $45 per page to pencil and ink, but not the bonus money he was looking for.”

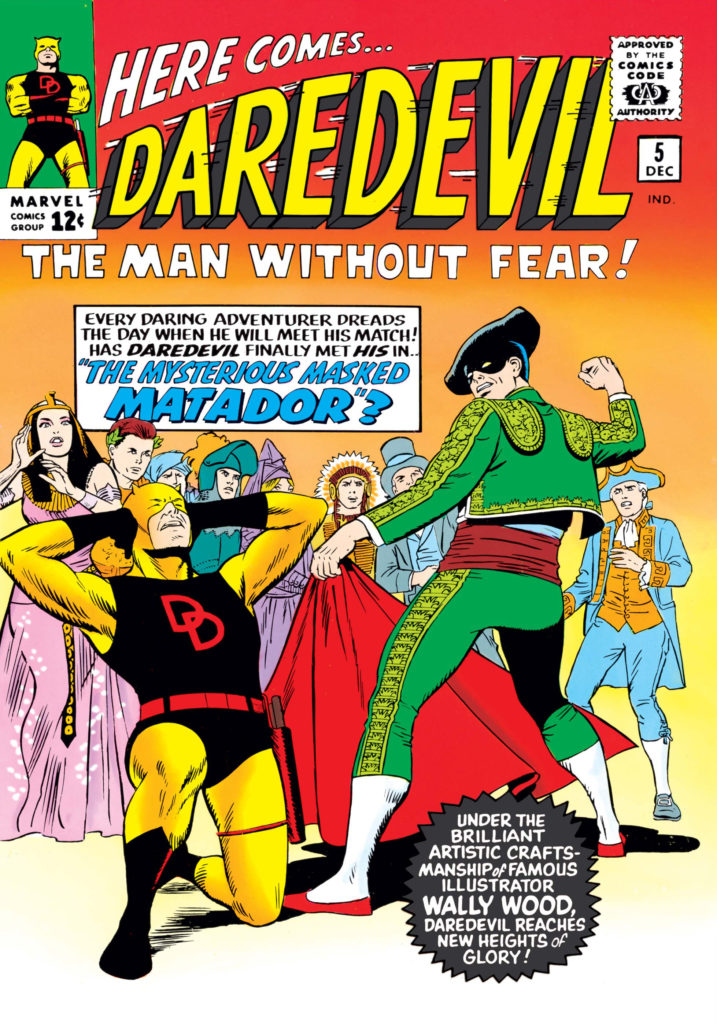

Wood was so popular that on the cover of Daredevil #5, his first issue at Marvel, they added a large badge promoting him: “Under the brilliant artistic craftsmanship of famous illustrator Wally Wood, Daredevil reaches new heights of glory!”

That kind of promotion from your publisher is incredible, but it’s hard to ignore the fact that Wood took a 75% pay cut for it. He had just turned 37 years old, and if he wanted to make the same money he’d made for a single page at MAD, he needed to produce four pages at Marvel! So you can understand why he might be interested in increasing his efficiency.

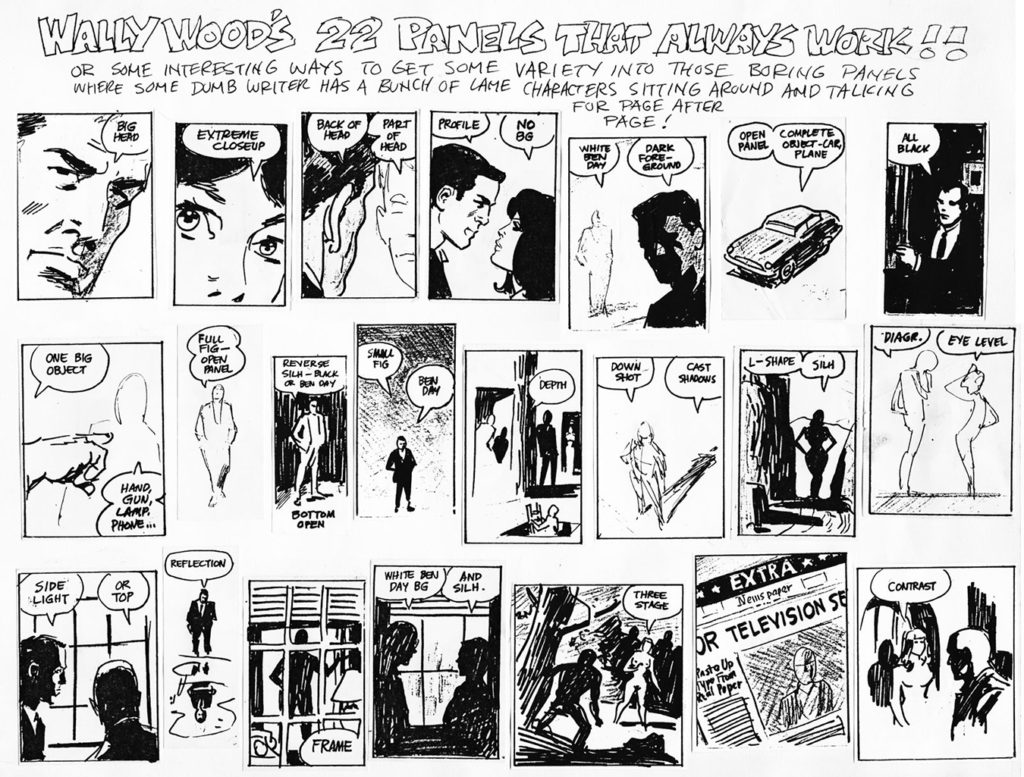

He would sometimes give his assistants sheets with examples of layouts that “bore the absolute essence of drawing comic book panels.” These bits of visual shorthand enabled an artist to quickly produce work without overthinking things.

The message was a simple one: We’re not being paid enough to spin our tires. Here’s a constrained set of proven ideas. When you get stuck, pick one and move on.

The “22 panels” we know today were assembled by one of Wood’s assistants, Larry Hama: “When I was starting out as an editor at Marvel, I found myself in the position of having to coach fledgling artists on the basics of visual storytelling, and it occurred to me that the reminder sheets Woody made would help in that regard.”

According to an auction listing for the panels, “[Hama] ran off 50 copies, and handed them out to potential pencilers. Pretty soon, other editors were sending pencilers and even some old pros down the hall to get copies from him. Eventually, he had more master copies made and gave them to other editors so they could make their own copies to pass out… Second, third, fourth, tenth and twentieth generation copies continued to be made and handed down.”

Hama later said, “I don’t believe that Woody put the examples together as a teaching aid for his assistants, but rather as a reminder to himself. He was always trying to kick himself to put less labor into the work! He had a framed motto on the wall, ‘Never draw anything you can copy, never copy anything you can trace, never trace anything you can cut out and paste up.’ He hung the sheets with the panels on the wall of his studio to constantly remind himself to stop what he called ‘noodling.’”

The “22 panels” became legendary in the comics industry, with many, many homages and tributes produced over the years. All because an artist who took a pay cut for a new job was looking for ways to increase his output.

As a developer, I think of Wally Wood all the time. Not every bit of code needs to be precious. When I create a template or abstract a pattern into a component, I’m avoiding writing the same code twice. When I add a linter, I get to spend less time thinking about code formatting. When I write tests, I’m reducing time spent confirming everything works.

How can you reduce “noodling” in your work?